Originally published In The Chronotype, February 2015.

One of the most popular TV series of recent years, The Walking Dead, is beginning its sixth season. Sheriff’s deputy Rick Grimes and his intrepid group of zombie apocalypse survivors are still on the run from the hideous “walkers,” searching for a safe haven. Whether they eventually find it depends on how long the producers think they can string the story along. So far, it looks like Grimes and his people will keep running.

The story is violent and gruesome. Not only does Rick have to contend with the mindless zombies, he must deal with treachery within the ranks of the survivors. It’s one calamity after another with no hope in sight. Why do they keep going against such terrible odds? Well, considering the alternative, I’d probably keep struggling, too.

Dealing with calamity back then.

The series, and recent zombie movies like World War Z, are examples of dystopian fiction, a popular theme these days on screen and page. The dictionary defines “dystopian” as, “An imaginary place or condition where everything is as bad as possible.” The opposite of “utopian,” in other words. It’s not a new genre; classic novels like 1984 and Fahrenheit 451 were published decades ago. Recently I revisited another one, Costigan’s Needle, published in 1953. I’d read it in high school, and now I was struck by how different it is from today’s examples of the genre, a reflection of how society has changed since those days.

In the novel, an eccentric physicist has invented a machine that sends any animate object sent through the Eye of the Needle to…somewhere. Backed by a large electronics firm in Chicago, Costigan builds a Needle large enough for a human to walk through, but the first few who go through don’t come back. Then something goes wrong, of course, and every living thing within several city blocks is sucked through the Eye.

What happens next reflects the story’s early-fifties origin. (Spoiler alert!) The people find themselves on the forested shore of Lake Michigan in an alternate universe, apparently uninhabited by humans but filled with wild game and plentiful resources. Led by the executives and engineers of the electronics company, the displaced Chicagoans quickly get organized and within months have built a frontier outpost with 20th-century conveniences like steel and glass. They embark on a quest to build another Needle and get home.

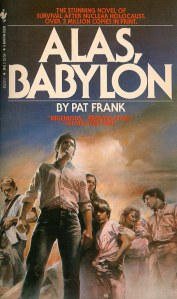

Another great example of the genre and period is Alas, Babylon, written in 1959 by Pat Frank. A small town in central Florida faces the aftermath of a nuclear war. Untouched by the conflict directly, the citizens of Fort Repose have to deal with a world that quickly runs out of electricity, gasoline and medical supplies. But they hang in there; unlikely leaders emerge and the town faces its uncertain future with determination and hope.

Dealing with calamity now.

Costigan’s Needle was written by the late Jerry Sohl, who wrote a number of scifi novels in the fifties and later penned episodes for shows like Star Trek and The Twilight Zone. If Sohl were around today, though, he would have to write a different kind of story. There would have to be racial tensions, sexual escapades, a takeover attempt by the police lieutenant and his men. Instead of banding together to survive and indeed thrive, the survivors would struggle to keep anarchy at bay.

So, which version is more realistic? I’d like to believe Sohl’s original vision is the likelier outcome. With literally nothing but our intelligence, experience and willingness to work, could we do what Sohl’s Chicagoans and Frank’s Floridians of the fifties did? One big plus is that we wouldn’t have TV, so that means no MSNBC or Fox News to tell us we shouldn’t trust each other. Imagine a world without O’Reilly and Maddow, Hannity and Sharpton. Where do we get in line?

On “reality” TV shows, people usually don’t get along. But in the real “reality,” we Americans usually do, events like Ferguson notwithstanding. We have our disputes, certainly, and once in a great while they get pretty serious, but by and large we have been able to work together. Maybe the difference is that in Sohl’s day we weren’t constantly being told that we can’t.