It is March, which means the end of winter and arrival of spring, baseball training camps in full swing, and millions of Americans are bewitched by the sound of a round ball swishing through a net. For this month, from coast to coast and north to south, basketball reigns.

Basketball has been an important part of my life every March since, well, pretty much as long as I can remember. I attended my first game when I was in kindergarten and my father was a teacher at St. Francis High School in a small suburb of Milwaukee. I was only five years old but everything about the spectacle entranced me: the uniforms, the cheerleaders, the scoreboard, the gymnasium, the crowd. From that moment on, I wanted to be one of those players, wearing that uniform, playing the game, hearing the cheers.

The game was a lot different back in the sixties, especially for kids. There were very few organized leagues, no summer camps, no overheated social media anointing third-graders as future NBA superstars. The NBA itself was little more than a blip on the national sports radar, a small collection of teams that was dominated by the Boston Celtics, who won eleven championships in 13 seasons from 1957-69. Major college ball was hardly any different. Big-city schools ruled the roost and the National Invitation Tournament, held in New York, was even more prestigious than the one that crowned the official NCAA champion.

Hoosiers, a few years later and further north.

Growing up in southern Wisconsin, my exposure to basketball was largely through attending the games of the schools my father worked for, ranging from large suburban gyms in places like St. Francis and Cudahy to cramped, dimly-lit bandboxes in Cambridge and Seneca. It was at the latter school, where my dad was principal for the 1964-65 school year, that I learned how to run a scoreboard. Dad would open up the gym on Saturday mornings for pickup games and I would go along. One time I talked him into hooking up the scoreboard, an old antique with an analog clock, and letting me run it. I was in second grade. It was also then that we found out I needed glasses; the numbers were blurry and I had a hard time counting the lights that were burnt out.

My fifth-grade year, ’67-68, was spent in Cudahy, another Milwaukee suburb, and our elementary school, J.E. Jones, began an after-school intramural league that winter. It was a big thrill when I was selected to be on the team that played a handful of games against other schools. We had no uniforms, just tie-down bibs with numbers that we wore over our T-shirts, but it was the big time at last. We played real games with real referees in front of real fans and the scoreboard, by golly, was tallying up the baskets we ourselves were making. There was also a Saturday-morning league at the high school, and at season’s end I was selected to play in an exhibition at halftime of a high school game. For this league we had real jerseys and to say it was a thrill to go out there on the big floor was a serious understatement.

After that school year we moved to Potosi, a little town on the Mississippi River in the southwest corner of the state, and in seventh grade I got to suit up for our junior high team. We played a ten-game schedule and for the first time I got to play a real game on a high school floor. For my eighth-grade season we even had new maroon uniforms with white trim. I started every game for our “A” team both seasons and as an eighth-grader led the team in scoring at 14.9 per game, or something like that. Then it was on to high school, and the real life lessons began.

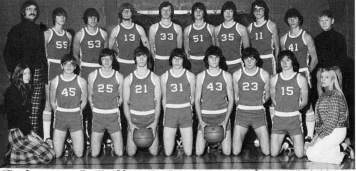

Suiting up for the Chieftains at last.

In those days a school had two teams, a varsity and a junior varsity. Only exceptionally-talented freshmen ever made the varsity, even in small towns, and while I was pretty good in those days and had some size (6-3 as a 15-year-old), I was placed on the JV team for my freshman season. Our coach was a young Chicago-raised guy named Wally Widelski. He drove us hard and sometimes we were terrified to come to practice, especially if we’d played poorly the night before. But by season’s end we had a pretty good team, finishing 11-7 (including a perfect 9-0 at home, a mark in which we took great pride). I led the team in scoring and rebounding.

It is said that a young person can learn a lot about life through athletics. In those days, when things weren’t nearly as structured as they are today, it was really up to the individual player to work on his game. Our town had literally no outdoor basketball courts back then, so in summertime I would walk the three blocks to the school and shoot around on my own in the gym. Two or three nights a week there was open gym for pickup games. But again, there were not yet any summer leagues outside of the cities, no AAU circuit, no camps. We were on our own. If I was going to be a good player and wear that varsity uniform and hear those cheers, I had to earn it the hard way.

That was a tough lesson, but in those days kids learned that lesson early on. Life was much more of a meritocracy, at least in small-town Wisconsin. Those who worked hard generally were the ones who found success. Nobody ever got tenth-place trophies. In fact, we rarely got trophies for anything. And sometimes, even when you worked hard, things didn’t work out for you. I learned that lesson at the end of my freshman season, when I was promoted to the varsity for the post-season tournament. Our school had never done much in the playoffs, but this was the first year our state had a division strictly for schools under 400 enrollment, and for the first time small-town Wisconsin kids could realistically dream of playing on the big floor at the UW Field House in Madison. I thought I could really help our team, which had once again finished around .500, but in our first sub-regional game against Cassville, our fiercest rival, I rode the bench as a fellow JV player, sophomore Danny Tobin, played a key role in helping us to a double-overtime victory. A few nights later we played Belmont, a team we had beaten twice already, and things were different. Tobin got the start and played well, but some of the upperclassmen didn’t really show up that night and we were trailing at halftime. I told Coach Widelski, who was the assistant varsity coach, that I was ready to go and if our head coach wanted somebody to rebound, I could get him some. I took off my warm-up jacket and was hitting shot after shot as we loosened up for the second half, and I was thinking that the dream I’d had so many years before would finally come true. It didn’t. I sat on the bench the entire second half and we lost. Bloomington, a team from our league, went on to win the first small-school title.

The following season there was really no question about which team I’d be on, although all of my classmates from the year before would play again on the JV team. I was on the varsity bench for our season opening game in Holy Cross, Iowa, but played quite a bit, and I started every game after that and had a pretty good season. The team wasn’t quite as good as we’d hoped to be, finishing 11-8 after a loss–once again to Belmont–in the first round of the playoffs.

Epic highs, and terrible lows.

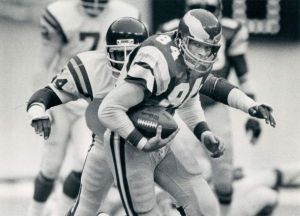

My father, the superintendent of the district, decided that a coaching change was in order, so Coach Widelski was elevated to head coach, to go along with the head jobs for football and baseball. The school ordered new uniforms for the upcoming season and confidence was high. I would be the only returning starter but our JV team had gone 14-4 without me and we all anticipated a strong season. Those hopes ended the night of October 30, 1973, when I suffered a serious knee injury in the first practice of the season. Two days later I had surgery and was in a cast for six weeks. Despite this and the loss of some other key players to less-serious injuries and illness, we were 4-4 as we approached the mid-season mark. Coach Widelski had promoted a talented freshman, Mike Krepfle, from the JV team. The Krepfle family was famous in Potosi for producing star athletes; Mike’s older brother, Keith, had just finished a stellar football career at Iowa State and would play several years in the NFL and score a touchdown in the 1981 Super Bowl. A younger brother, Bob, would set records as a quarterback at UW-La Crosse. Mike himself was a terrific football player, too, and would earn a scholarship to Wisconsin. With Krepfle in uniform and my return imminent, things were looking up.

I had my cast removed and began rehabilitation the next day, hobbling up to the school on a Saturday morning and walking endless laps around the floor in the empty gym, shooting some free throws, and dreaming of returning to action. These days I would’ve been on the shelf for the entire season, but back then things were a little more primitive, and by early January I was cleared to play. I suited up on January 11th, got into our game at West Grant and promptly twisted the knee leaping for a high pass. There was no physical damage, but the psychological toll was great. It was another month before I played again.

Meanwhile, the team faded. Perhaps the other players were also thrown into a funk by my injury situation, but more likely it was just a case of teenagers going through some tough times. By the end of February, though, I was healthy enough to play, had some confidence back and the team started to gel. Even though we finished the regular season 5-13, we got a bye through the first round of the playoffs (today they seed the field) and won our second-round game, a very satisfying defeat of Belmont. That put us into the regional round and up against Shullsburg, the co-champion of our league, a team that had already routed us twice. The game was in Cassville and the gym was packed to the rafters. Almost everybody there figured the Miners would handle us again and move on to the next round the following evening against Mineral Point, an unbeaten team from a larger league which had just dusted off Bloomington in the first game of the semifinal doubleheader. No doubt every Shullsburg player and fan in the gym thought they would be victorious once again over the lowly Chieftains. Certainly many of our fans were just hoping we would put up a respectable fight.

We actually thought we could win.

We hung with Shullsburg all game long, and as often happens when the underdog hangs around, things got interesting. In the final minute, we were trailing by one and our sophomore guard, Dave Kerkenbush, drove the lane and made a basket, but was called for a charging foul. These days they would not count the bucket, but back then they did, giving us a one-point lead. Shullsburg would now shoot a one-and-one from the free throw line at the other end. Less than 15 seconds remained. The Miners called time-out, then their top scorer sank both shots to put them back on top. We called our final time-out to set up the last shot. The play was for Kerkenbush, our best ball-handler, to get the ball into the front court and down low to me. But Shullsburg played it smartly, pressuring in the back court to use up time. With the clock running down Kerkenbush crossed the half-court stripe in the corner near the scorer’s table as I was banging for position underneath, but there was no time for a pass and he launched a 40-footer. I can still see it ripping through the net. The Miners stood there, stunned, as the horn sounded and our fans charged the floor.

That game still lives on in school legend, and like most legends some of it is fact, some fiction. One story is that Kerkenbush was attacked by the Shullsburg cheerleaders in the melee after the shot. Another is that Shullsburg sent the wrong player to the line to shoot those free throws. I’m not sure about the cheerleader story, but I know for a fact the free-throw tale is true. We saw it watching the tape of the game a few days later (our school had just gotten a bulky reel-to-reel video recorder), and during my college days I ran into a former Miner—the guy who got fouled, as it turned out—and he confirmed that in the huddle during the time-out the coach told the top scorer that he would be shooting the free throws. The referees never saw it and that almost cost us the game.

Seventeen years later I was broadcasting the state Division 4 championship game in Madison between Shullsburg and Spring Valley. I introduced myself to the Shullsburg coach, the same guy who’d coached the Miners against us back in my day, and he recognized me. I didn’t ask him about that time-out in Cassville.

The day after the epic win we had a light workout in our gym and ended it by practicing something every basketball player dreams of doing: cutting down the net. But that night back in Cassville, reality returned. Mineral Point walloped us on the way to their runner-up finish at State in the small-school division. We finished 7-14. To this day I think that if I’d not suffered that knee injury and if my other teammates had stayed healthy, we would’ve had a much better season. Mineral Point wouldn’t have blown us out, that’s for sure.

The following season we turned that around. Everybody was healthy and hungry. Those of us not on the football team worked out every day after school in the fall and we were in great shape when practice started in November. We ripped off a five-game winning streak to start the season, laid an egg at Shullsburg that started a four-game skid, but went 7-2 in the second half of the season to go into the playoffs on a roll. I had an all-conference season and we were thinking of Madison, or at the very least La Crosse, which was where the regional winner would go for the sectional, the last two rounds before State. Our mid-season slump cost us the Blackhawk League title we thought for sure we’d win, but the playoffs would be another story, we were sure. Things started out well with a couple wins in the sub-regional round, an 18-point thumping of Shullsburg followed by a bizarre game with Benton, in which they held the ball on us and we won 12-6. The regional would be held at the home of our old playoff nemesis, Belmont, and we would face the host Braves in the semifinal.

It was a snowy Friday in early March, 40 years ago now. School had been called off because of the snow but the game was still on. (The next year the same thing happened and they moved the games to Saturday night.) A couple cars got stuck in front of our house, and in casual teenage defiance of Widelski’s warning against doing anything strenuous on game day, I pushed them out of the snow. That night in Belmont my shot was gone. I came into the game averaging about 16 points per game over the final month of the season. My mid-range jumper was deadly and almost impossible to defend, but that night, zip. I had one point, on a free throw in the second half. Even without anything from me, though, we had an 18-point lead on Belmont late in the first half. The Braves closed to within 12 at intermission and we fell apart in the second half, losing by seven. Or maybe eight. I haven’t looked at my scrapbook in years and have no desire to relive that game, much less find out the final score.

The dream I’d had since kindergarten, of playing high school basketball, was over.

March Madness lives on.

One thing that few if any teenagers ever have is perspective. Their world is happening right now, and if they think of the future at all it is only a year or so down the road when they can move out, go to college and have even more fun than they’re having in high school. It’s only through the passage of time that we can properly think about those four short years, the friends we had, the things we learned, both in the classroom and out. I still have some valued friendships from those days and eagerly anticipate our reunions. I stay in touch with Coach Widelski, who left Potosi in 1976 for Galena, a larger school in northwest Illinois, and then returned to Chicago where he is now retired. He remains one of the handful of influential men in my life, on the next level right after my father and grandfathers.

After high school I went to college at nearby UW-Platteville. Declining a chance to play on the basketball team, a decision I rue to this day, I got a degree in radio-TV broadcasting and embarked on a career that I felt was destined to land me a job as a play-by-play voice for a major college or pro team. Over the next 20 years I broadcast hundreds of high school and small-college games, but never made it to the big time. But some doors open and some don’t. The ones that opened led me to the place I am now, and I wouldn’t trade it for anything. Even though I left full-time radio work back in 1999, the local station still calls on me to help out now and then, typically during the basketball playoffs, where once again I witness the thrill of victory and the agony of defeat, now experienced by kids who probably think 1975 is ancient history, if they ever think of it at all. If somebody had come up to me during my senior year and said, “You know, I played ball here 40 years ago,” that would’ve been 1935, and we would’ve wondered if they still had laces on the ball back then.

Nowadays I spend a lot of March evenings and afternoons watching the Wisconsin Badgers play on TV. Today they will go up against Michigan State with the Big 10 tournament title on the line, and later this evening we will find out where they will be going for the NCAA tournament. In my youth, the Badgers were the doormat of the Big 10, but not anymore. The program was resurrected by Dick Bennett in the mid-90s and now Bo Ryan, who coached my alma mater, UWP, to four Division III national titles, has the Badgers on the brink of a national championship. It could be an epic March for Bucky fans.

Although my knee injury was no walk in the park by any means and that last game against Belmont still bothers me, I have, hopefully, gained the proper perspective. The injury and the rehab taught me that bad breaks happen and you just have to pick yourself up and keep going. I found out a lot about myself in those few months over the winter of ’73-74. The next season taught me that if you want to have a real shot at ultimate success you can never let up. Yes, my shot was gone that night but I could’ve compensated by driving to the hoop, getting some layups and free throws, and we might’ve won that game, beaten Bloomington for the regional title the next night and who knows, we might’ve won it all. Probably not; over 400 high schools competed in basketball that season in Wisconsin and at the end, only three teams, one in each division, raised a big gold trophy. Everybody else got beat, but that does not mean they were losers. We were not losers, either. We carried the banner of our school and town proudly, and in fact we set a record for victories that was equaled by the ’76 team but not eclipsed for a quarter-century.

A few years ago, Potosi celebrated the 50th anniversary of the school by inviting every all-conference athlete in school history to Homecoming. Sue and I drove down and I showed her my old school and gym with great pride. The celebration that evening was very special. I remember running into a current student who asked me about our team, and how we would compare to today’s Chieftains. After all, today’s kids are a little bigger and a little stronger. They have the benefits of weight training and nutritional science that we never had, they have all those camps and summer leagues and nice outdoor courts to play on. What would happen, I was asked, if my Chieftains from 1975 played the modern version? “You’d probably beat us,” I said, “but you know, we’re all in our fifties now.”

Thank you for the auspicious post. I really enjoyed it.

I look forward to seeing more content from you!

How could we keep in touch?

Check out the “Links” page for links to my social media sites, or you can email me directly via the contact page. I look forward to hearing from you!

My brother recommended I might like this web site.

He was once totally right. This publish actually made my day.

You can not believe simply how much time I had spent for this info!

Thank you!

Greate pieces. Keep posting such kind of info on your site.

Im really impressed by it.

Hi there, You have performed a great job. I’ll definitely digg it and

personally recommend to my friends. I’m confident they will be

benefited from this site.