My two brothers and I have often talked about how blessed we were, growing up with both of our grandfathers close by. It’s a situation our own kids were never able to know, showing how increasingly rare it is in today’s American society, with no signs of that getting any better. Our grandfathers have now been gone for nearly 40 years, and two of us are now grandpas ourselves.

Our dad’s father was James L. Tindell, born in Platteville, Wis., in the spring of 1902. In the second year of the 20th century, America was a much different place. Theodore Roosevelt was less than a year into his presidency. The frontier had been declared officially closed only 12 years before. The end of the Civil War was only 37 years in the past, closer to people then than the Vietnam War is to us today, and its surviving veterans, including newborn James L.’s own grandfather, were still in their fifties and sixties. Their memories of Abraham Lincoln were more recent than ours of John F. Kennedy are for us today. The Wright Brothers were a year away from their first flight, Babe Ruth was a seven-year-old kid in Baltimore, Kaiser Wilhelm II was emperor of Germany and World War I was twelve years in the future. Many of the titanic figures of the coming century were young men (Winston Churchill, Albert Einstein, Douglas MacArthur), just kids (Franklin Roosevelt, Dwight Eisenhower, Adolf Hitler) or yet to be born.

Young James married Leona Speth, the daughter of German immigrants, in 1923, when he was 21 and she was 17. Their first child, a son they named Ernest, came along two years later, the first of a brood that by 1936 would include one more son, our dad James Jr., and four daughters. James L. worked a lot of jobs: he was a lead miner like his father, drove a cab, installed siding on houses. By 1940, the year he turned 38, he was an auto mechanic and, according to the census, supported his family (including his mother-in-law) on about $150 a month. After World War II, with their youngest kids still in elementary school, James and Leona got jobs at a factory in Dubuque, Iowa, about 20 miles to the south, where they worked making pots and pans. It would be their last and best jobs, all the way to their retirement in the mid-sixties. Their final home was a very small 2-bedroom house on Hickory Street in Platteville, next door to the slightly larger home in which they’d raised their family before selling it to their second daughter, Alice, and her first husband.

A hundred miles or so to the east, and 14 years later in 1916, our maternal grandfather, Alvin Carpenter, was born. He was from the small town of Palmyra, not too far from Milwaukee in terms of distance but a world away in terms of culture. Alvin was a small-town kid whose own mother died in a traffic accident when he was young. In 1934, when he was still in high school, he married a farm girl a year his senior. Meta Hohnke, like Leona Speth, was the daughter of German immigrants; her father had come to America to avoid service in the Kaiser’s army. Meta grew up in a home that had no electricity or running water until her teenage years. A tall, strapping young man, Alvin took whatever manual labor jobs he could find to support his young family during the depths of the Depression. At one time he shoveled coal from railroad cars for a dollar a ton. Their first child, my mother Sandra, was born in 1936. Four siblings would follow; two of them would not survive childhood, something Grandpa never talked about. A short time after my mom arrived, Alvin got a job with the Milwaukee Road, beginning a 40-year career as a depot master in various small towns throughout southern Wisconsin. In World War II he had a deferment due to his work in a vital industry, and work he did, often 12-15 hours a day, seven days a week, to keep the trains running. He told me that despite that status, he was actually notified in the spring of 1945 that he was to report for induction, but it was rescinded at the last moment. I told him that he would likely have been sent to Europe for occupation duty after Germany’s surrender, to replace the veterans being sent to the Pacific, and he said he didn’t even think of that; he was sure he would wind up on some island fighting the Japanese and might not come home. Every few years the family would move, eventually winding up in Platteville in 1953, just before the start of my mother’s senior year of high school. A few months later she met a 1952 graduate, young Jim Tindell. They married in the fall of 1954 and started their own family when I arrived two years later while Dad was serving in the Army in Germany.

The deaths of my grandfathers were the most devastating experiences of my young life at the time, occurring as they did less than two years apart. Grandpa Tindell was out in his yard, picking up walnuts, on a fall day in early October 1978 when he suffered a heart attack. Grandma saw him on the ground and called an ambulance, getting him to the hospital in time to save him, but it was short-lived. Four days later my father was waiting in the lobby, having just arrived after a four-hour drive from his home in Hudson, when he saw the heart monitor flat-line. I was a senior in college and working in the press box at a football game on campus a couple miles away; I knew Gramp was in the hospital but had decided to wait till the next day to visit him. Neither me or my dad got a chance to say goodbye. His funeral a few days later was the first I’d ever attended.

Early in 1980, I was living out in Montana when my father called to tell me that Grandpa Carpenter had been diagnosed with cancer. A cure was unlikely. Grandpa had been a smoker until having heart-bypass surgery in 1970; a few years later he had a melanoma removed from his throat, but it came back, and by the time it was spotted, it was too late. I got back to see him in March of that year; he passed away in early June. The day he died, after getting the dreaded phone call from Wisconsin, I climbed a mountain outside Missoula and sat there for a couple hours, thinking of him, and more than a few tears were shed.

Men of simple dignity and honor.

My brothers and I have six children between us, and none of them were able to meet our grandfathers. My own kids have occasionally asked me about them; what kind of men were they?

Well, they were simple men, to be sure. James L. had quit school after sixth grade to go to work to help support his large family. College was something reserved primarily for the rich and well-connected back then, even though there were two right in Platteville, a mining school and a normal school, for the education of prospective teachers. Gramp told me that when the schools’ football teams faced off, it was brutal. He never flew on an airplane, and as far as I know never left the United States, not even to Canada, a day’s drive away. When my folks moved up to Hudson a few months before Gramp died, my father offered to pay for a flight from Dubuque up to nearby Minneapolis and back, but Gramp said no. Yet this man, born before the first airplane flight, got to touch the skin of the spacecraft that took men to land on the moon. In 1970, a year after the landing, the Apollo 11 capsule came to Madison as part of a traveling exhibit, and my father took his parents and his own family there to see it.

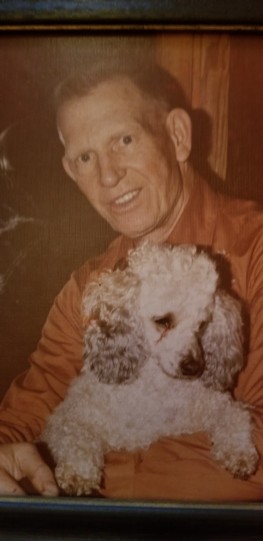

I’m sure Gramp never had much money, but he never complained about it, never once said it was unfair that some people in town got to live in bigger houses and drive fancier cars. He took his pleasure in hunting and fishing with his sons and sons-in-law and grandsons; he and Leona’s six kids produced 18 grandchildren, all of whom lived in or nearby Platteville. Their house on Hickory Street was a gathering place for the clan. On any given Saturday people would be dropping by all the time. It was in their living room we got our first glimpse of color television, around 1965 or so.

In the early sixties Gramp bought a small fifties-era mobile home and moved it to a little fishing village on the Mississippi River called McCartney, about a half-hour drive from Platteville. It had electricity but no running water. Bathroom facilities, such that they were, consisted of a two-hole outhouse that was always infested with hornets, making visits there especially exciting. Fresh water was obtained from a communal spigot that served the few cabins and houses that nestled along the creek that came in from the river. Gramp’s boat, a 14-foot flatbottom with a 15-horsepower outboard motor, was tied up to a small dock he’d built himself, about twenty yards from “the trailer,” as we always called it. During the season Gramp and whatever Tindell menfolk were available would head out on the river to fish. If there were no men around, Grandma would go, always using a cane pole. We’d bring our catch back to shore and clean them at a little shed he’d also built. Grandma would fry them on the gas stove in the trailer and we’d eat. If we stayed overnight, we’d try to watch TV on the small black-and-white set with a rabbit ear antenna, and if a storm rolled across the river, the thunder would roar and the trailer would shake. Through it all the adults would play cards around the small table and tell stories. Those days were the best of times.

I did a lot of hunting and fishing with Grandpa Carpenter, too. We’d take his boat down to McCartney, launch it in the creek and head out onto the mighty river, cruising among the islands. Once in awhile we’d go all the way over to the Iowa side, tie up at a tavern’s pier and head inside for a hamburger. We might put in off “The Point” near Potosi, or even go east to fish one of the few lakes in that part of the state. One summer, when I was about 16, Gramp and I drove across the state to Algoma, where we went out on Lake Michigan aboard a chartered fishing boat and caught some big ones, although I can’t remember exactly what they were. Lake trout, maybe. During spring break of my freshman year in college, we drove down to northern Alabama to spend a few days at the home of his younger daughter, my aunt Linda, and her family, fishing on the meandering Lewis Smith Lake. Gramp had an old ’66 Ford sedan that we drove down there, and shortly after we got back to Platteville he gave it to me.

Alvin’s years of smoking led, predictably, to health problems that resulted in his heart-bypass surgery. Back in 1970 it was risky indeed, but he survived and we had another ten years with him. Over the course of that decade, as I went through high school and into college, I was able to spend a lot of time with him, and the conversations we had still resonate with me. I was able to talk to him about things I couldn’t bring myself to discuss with my own father. In some ways I felt Gramp understood me better. Like virtually every teenage boy I wasn’t willing to cut my own dad much slack, but my grandfather was on another plane.

James Tindell and Alvin Carpenter had much in common. They were small-town Wisconsin guys who had to work hard for everything they ever had. In terms of material wealth, they didn’t have much, certainly not as much as many other people had. But they never complained about their lot in life, never demanded anything be handed to them, never felt they deserved special treatment. They married young and raised families through the depths of the Great Depression and the struggle of World War II. Most people today have no living memory of those events and really cannot imagine what it was like. Our lives today are lavish and secure by comparison.

My brothers and I often speak of our grandfathers and agree that the lessons they taught us were mostly learned by our observation of them. They were men of simple honor and dignity. They got along with everyone but weren’t afraid to take a stand when a stand needed to be taken. They loved their wives and their children and their grandchildren and worked hard to support them. When they died, their funerals were simple affairs, and their obituaries never made it past the local newspaper. They were never the subject of TV documentaries or magazine articles. They wouldn’t know what to make of today’s technology that allows even the most obscure people to gain fame and sometimes even fortune for saying or doing outlandish things that can be tweeted around the world in seconds. They were men of a simpler time, and often I think that it was, in many ways, a better time.

And now, I am a grandfather, too.

A new era in my life begins.

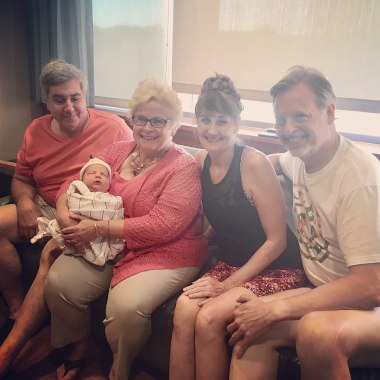

Last Christmas, our daughter Kim and her husband Mike gave us the best present ever: the announcement that they were expecting their first child. The next six months seemed to pass quickly. We visited them at their home near Boston over the first weekend of June, enjoying our time together and attending Kim’s baby shower. After our return, the countdown to the birth of our grandson began. The original due date was July 12, and we made plans to fly there for the birth, but then things were moved up a week. Six days early, Kim delivered a healthy 9 pound, 8 ounce lad they named Pasquale James Marolda, after their paternal grandfathers.

We flew to Boston the next day and were introduced to our grandson when he was about 26 hours old.

Over the next couple of days we were able to spend time with him at the hospital. Kim was doing well and new dad Mike was doing yeoman work helping out. We returned to Wisconsin on the 10th, and the new parents were able to bring little “Pax” home the next day. As of this writing, all is well at their home in the comfy suburb of Melrose. Pax weighed in at an even 10 pounds today at the pediatrician’s office.

Fortunately, Mike’s parents live in the next suburb over and will provide a regular grandparent presence for the lad. They’re good people and already have experience; Mike’s older sister has three kids.

I had always wondered what it would be like to hold my first grandchild. Pax was born 31 years and 1 day after our son Jim entered the world, and back then, somewhat overwhelmed with the knowledge that I now had not just one but two kids to care for (Kim was 5 at the time), 2018 seemed like a very long way off to me, if I thought about it at all. New fathers are frequently intimidated by this awesome new responsibility, and some of them can’t handle it, which is truly a tragedy. Failure was not an option for me, though, not with the example of my own father and grandfathers to inspire me. I think Grandpa Carpenter once told me that a man’s most important responsibility was to care for his wife and children. He was certainly right about that, as he was about so many things. Many times since his death, I have thought of him and Grandpa Tindell, especially when things haven’t been going particularly well. What would they think of this situation? What would they advise me to do? Something always comes to me: “This is what he’d do.” My own father also has a big part in that scenario. I have been so blessed to have such fine men to show me the way, and I hope I have been able to pass their lessons along properly to my own kids. By all accounts, I’ve been successful, sometimes in spite of myself; Kim and Jim have grown into fine young adults, with college degrees in their pockets and solid careers underway. Most of all, they are young people who have a strong sense of personal integrity. That alone will carry you a long way, especially in today’s world, where integrity often seems to be a thing of the past.

And now, I have a grandson to teach, to inspire. I told my father after Pax’s birth that when the little guy is the age Dad is now (83), it will be the year 2101. My grandson will likely see the 22nd century, and a year after that century arrives he’ll note the 200th anniversary of his great-great-grandfather James L.’s birth. The world will be different in many ways by then, but I’m confident some things will stay the same. Young boys will still need guidance by their grandfathers, and as the boys grow into young men, that guidance will hopefully take hold. As those young men age, they will remember what their grandfathers taught them, and eventually they’ll be able to pass those lessons along to their own grandchildren. The knowledge and wisdom will transcend generations. Consider that James L. Tindell’s own grandfather, William, was a Civil War veteran who died in 1916. Assume little Pax will have his grandson when he’s my age, meaning my great-great-grandson will be born in 2079. And that lad, if he lives to my father’s age, will see the year 2152, nearly 300 years after his ancestor marched south with the 43rd Wisconsin to take on the rebels in Tennessee.

The line moves ever forward. I never really talked to Grandpa Tindell about his own grandfather. Did old William tell the lad stories about his Civil War service? Surely, though, young James learned some things from the old veteran, things he passed along to his own son and thus to me. I passed them along to Kim and will hopefully have many occasions to spend time with young Pax. There will be fish to catch and baseballs to toss. He’ll learn how to throw a proper roundhouse kick and shoot a free throw. There will be trips to the ballpark and the county fair, and so much more.

It was tough to say goodbye to the lad that day in the hospital. We’d been able to spend time with him in every one of the first three full days of his life, but it will be a few months before we’ll see him again. I will somehow have to be a long-distance grandfather, something James L. and Alvin never had to do with me. But with their example to follow, that’s a hurdle I’m confident I’ll be able to overcome.

Just read the article . We will copy it and send it on to Scott and Steve. We receive messages from Scott. It gives us history on their Grandfather. They also have great memories of their grandfather. We are making memories here in Alabama for our granddaughter now before she leaves for the UAE in August. Aunt Linda

This is just plain lovely. What a gift.

Thanks, Mary, glad you enjoyed it.